Last September at Hatch Conference I had the honor of giving the opening keynote: Design & (Blank).

If you’re interested in speaking I highly recommend it. Call for Proposals

Last September at Hatch Conference I had the honor of giving the opening keynote: Design & (Blank).

If you’re interested in speaking I highly recommend it. Call for Proposals

One of the top questions I get asked is what a portfolio for a manager should look like. Unsurprisingly, the answer is like any design answer: it depends. The ultimate output of a portfolio looks different based on so many factors: whether you’re in brand or product, the type of management role, and what you’re optimizing for.

In this session, we’ll look at the goals of a manager’s portfolio, what you are optimizing for, and the core elements of a portfolio. There are a few common artifacts you’ll have as a manager: resume/cv, portfolio deck, and website. The last two might be the combo of your portfolio.

The truth is at some point in your management career you will not need a portfolio! You will be reached out by recruiters or apply based on your experience and credibility, which is a much harder thing to maintain than a portfolio!

You might be optimizing your portfolio for different reasons than looking for a new career opportunity. For example, you might want to get into public speaking at meetups and conferences. The content you show there is going to be much different than what you show in a career portfolio.

A leadership portfolio might not be optimized for looking for work.

Depending on the level or the role, you may or may not show the work you directly contributed to. For example, if you’re interviewing for a product design manager role at an early startup or at an agency, it’s very possible that part of your responsibilities is doing the work. If you’re interviewing for a VP of Design role, you won’t be showing any pixels you pushed (at least I’d hope not!)

Building a portfolio takes a lot of time, but you can start capturing data of what you’ll put in it as you go along. As a manager, the type of impact you make looks different than when you were an individual contributor (IC). Your IC portfolio is more around your work, process, and craft, and the management portfolio focuses on how you manage towards outcomes leading a group of humans. Keep an Infinite Slide Deck to track your work.

Journal your experiences as you’re doing the work. It’ll help you keep track of data and moments you want to share later. Trust me, it’s hard to remember later on. As you keep your journal, capture key metrics you’ll need to remember to tell the story.

My portfolio is a keynote deck. You can use anything that can be exported as a PDF you can share. I also highly recommend building a website that will be your digital portfolio. The website can serve as general content and portfolio deck can be more details. You may not want to disclose every single detail of your portfolio online and that’s where a website might serve better to speak at things for a high level. It’s common for design managers to have absolutely no portfolio published online.

I recommend having a website and a presentation deck ready to go. The content does not have to match 1:1 but it’s nice to have a website where you can have a general overview and a deep dive slide portfolio.

What is important in your portfolio

A few images and slides on your approach to management. This might include your leadership philosophy, what methodologies you subscribe to, etc.

Company and role overview

Case studies are different for managers. Though you’ll show project work (presumably what you did leading your team), the story you tell is slightly different. The core elements are:

This can be a complement to your slide deck. I recommend managers have a website. Elements to include:

The section that includes details about you:

I recommend that managers have a blog, whether on their personal website, or Medium. Writing articulates what it’d be like to have you as a manager or your philosophy. A few examples of good ones:

Work: Case studies and portfolio pieces you might want to include online. Be mindful of the company metrics you share publicly in case it’s confidential

By the end of the management cohort, we’ll work on your portfolio, your about page, and one case study of a project you led.

There are no one-size-fits-all approach for a leadership portfolio. However, here are some tips to keep in mind as you build your portfolio.

Focus on outcomes and impact; present your work at a level higher than you might be used to. Your portfolio will look more like case studies of your time at the company and with your teams vs. individual projects.

It’s okay to show the work of your team. In fact, you should. However, make sure you give them credit.

Even as a manager, people want to know you used to be a good designer! I recommend including a few pieces of content around your work when you were an IC. No need to go in detail and include this as part of your overview.

Part of what people will expect from leadership portfolios is the lessons you learned along the way. It will be more authentic if you talk about the lessons and address the “What would you have done differently?”

—

Originally posted on Proof of Concept

Without question, collaborative document editing for teams building products is here to stay. This shift has to do more with how companies operate than the product development process. When you think of collaborative software like Google Docs, GitHub, and Figma, they took the model of local-first software and make gave more access to people in the org to do work together. 65% of Figma’s users are non-designers, 3x’ing the amount of people using the design tool1.

Collaboration has revolutionized the way work is done. However, what I see get lost in the midst for doing work together real-time is time for people to think and develop a point of view. Frank Bach articulated this well in a tweet.

Something I see designers struggle with is not being comfortable with their own point of view. It's ok to have an opinion. It's also ok if that opinion is later 'wrong' and you change your mind.

— Frank ☼ Bach (@zendadddy) August 29, 2022

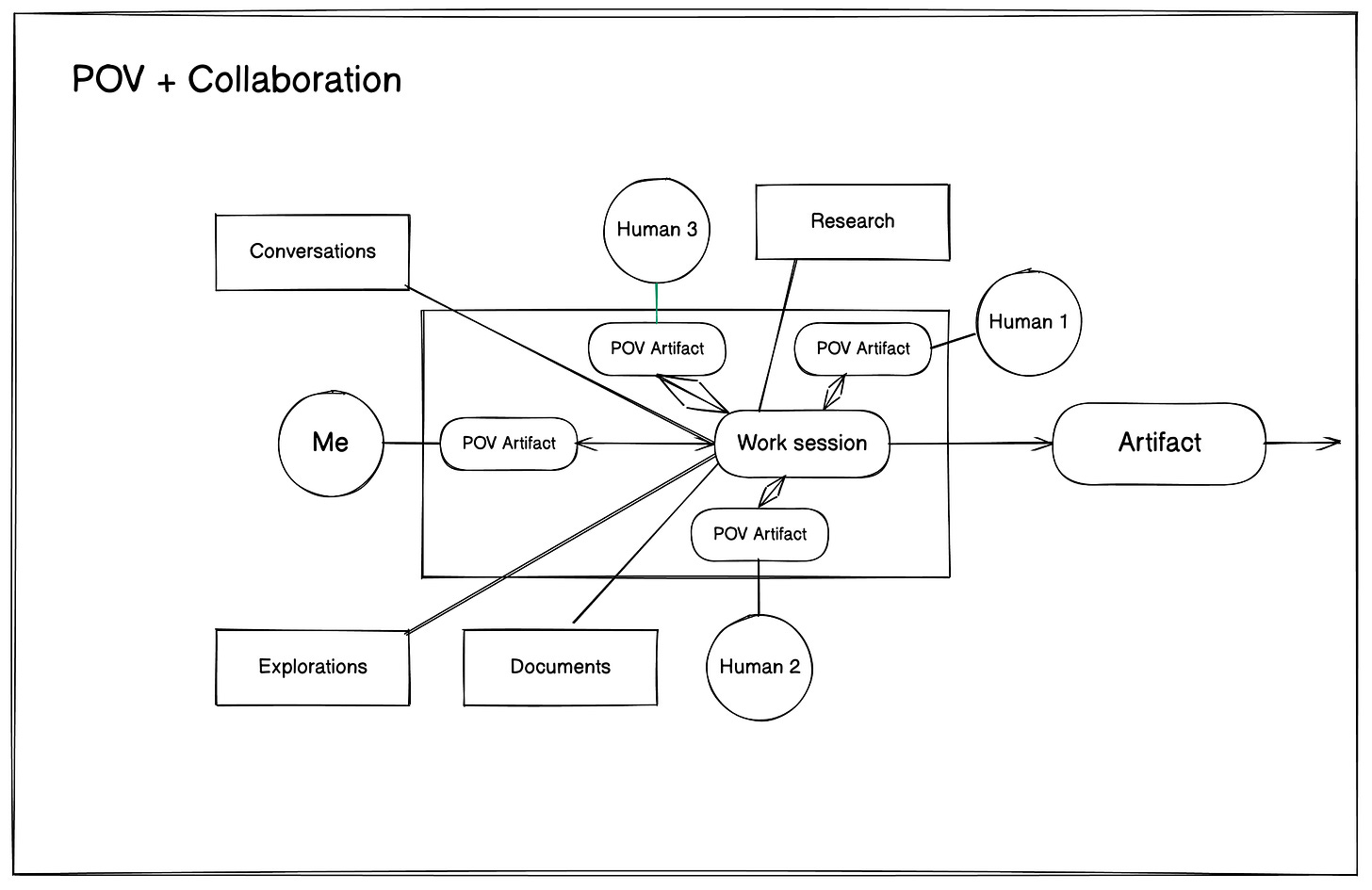

My hypothesis is by increasing the contrast of developing your personal point of view combined with collaboration can result in better team outcomes. Let’s cover some details of each one and what you (and your team) can do to mature these practices.

Having a strong point of view develops conviction what you believe in. Having a strong point of view doesn’t mean you need to act like the former CEO of Bolt. It’s about shining a beacon on what you believe and your point of view. People who have a strong POV can also be very open to collaboration (avoid binary thinking). It’s a way to share your observations on and your ability to pass on what you learn and share your point of view faster while embracing diversity of thought.

Though a strong POV is important, being open to integration points and feedback is key. This could be design critique, a pull request on GitHub, or product review. It’s critical to remember to share your POV as you’re working on it to ensure it can be integrated.

I use tools that are local-first or physical, and I may share snippets of the content to form an artifact vs. sharing the the entirety as an artifact. Some tools I enjoy:

Collaboration is the action of working with someone to produce or create something. Whether it’s a sports or product team, teamwork and collaboration is crucial in teamwork and achieve a shared outcome. As the African Proverb goes, ““If you want to go fast, go alone, if you want to go far, go together”. The super power of collaboration is thinking through ideas together, getting inputs, and unstuck.

When you’re stuck or needing a lot of inputs, there is no better way than putting everything on the desktop to work together. I’m a huge believer in pair programming/design, workshopping, and diverging to de-risk.

The biggest challenge in collaboration is what I call “The Convergence Melting Pot.” This phenomenon occurs when individual points of view get lost in collaboration and all inputs blend together. Avoid shipping “yes and…” whenever possible. Over-collaboration can result in unclear next steps or decisions. Who out of the entire group is the decision maker to move the work forward? Who will be held accountable for the outcomes?

The properties of great collaboration tools is a shared canvas, the ability to comment, and early visibility. A few collaborative tools I enjoy are:

Developing an independent POV and collaboration are effective tools to use and works better when the contrast between them is clear. Here are two suggestions on how to use the two effectively without blending them.

What occurs frequently in collaboration is what I like to call “the melting pot effect.” Like a fondue, a melting pot infuses and mixes everything as one thing. What results is what were clear inputs are blended in a something less intentional. Don’t build the car Homer Simpsons tried to build.

Instead of a Convergence Melting Pot, keep in inputs clear and work together to make decisions. The power of collaboration occurs when there are inputs and diverse points of view. Without diversity of thought, you’re no considering everything. Instead of a melting pot model, I prefer an input model.

On habit I’m forming is building my POV doc on topics to share with people. It’s specific and personal—used for an input for people to consider and make decisions. The nice aspect of a POV doc is often we are verbalizing our point of view without it being memorialized anywhere. I call the POV doc my Credo, the latin word for “I believe.” Your POV/Credo can be an input that influences a decision made and there is a clear correlation to it.

When crafting a POV doc:

Your POV doc can be a high level concept, such as “Visual Programming” or can be part of a Design Brief you generate.

In a world of easy access to multiplayer and real time collaboration, it’s easy to forget to establish your point of view. Developing your point of view and collaboration are both important. Make time to balance both and use them when they are most valuable.

I highly recommend reading the book Design at Work by Joan Greenbaum and Morten Kyng. Warning, it’s a great ready but heavy—making Thinking Fast and Slow seem breezy like a one-sitting read of a Goosebumps book.

Collaboration isn’t a nice-to-have, it’s essential. That said, get the right inputs, ensure perspectives are heard, and make the decision.Maximize it by developing your own POV to understand your perspective and those of your colleagues.

In the midst of the pandemic of COVID-19, many lives have been impacted in so many ways. Unfortunately many people have felt the impact of layoffs throughout the industry, including design. I’m offering up some of my personal time to review portfolios and resumes for those who find it helpful.

Disclaimer: Please note this offer is me as a person and not that of my role as Director of Design at Webflow. This means if you’ve applied to a role at Webflow I am not reviewing your application as a part of this rather free coaching/feedback.

If you're a designer and affected by a layoff at or working on your first role in brand, product, or UX, I'd love to offer my time to review your resume and portfolio.

— David Hoang (@davidhoang) March 19, 2020

My email is david[at]https://t.co/p8ja6Yst9Y. Let me know if there is any specific feedback you're looking for.

I studied Art History in college and find the liberal arts to be one of the biggest influences in my design career. One of my favorite eras to study is Baroque art. It often brought high contrast, strong asymmetry, aestheticized violence, and remixed symbolism in its works. It’s the Tarantino era of art history. One of the artist who first caught my attention at an early age was Michaelangelo Mersi, better known as Caravaggio.

The Catholic Church at the time were huge patrons of the arts and commissioned artist to create paintings of famous scenes during the counter-reformation. Caravaggio, is what you wouldn’t necessarily call a religious man, which made his works so fascinating to me; an amoral man and sinner in the views of the church, being commissioned by the church. He often left a lot of room for interpretation in his paintings. One of the famous ones is that of “The Calling of St. Matthew”.

The 10.5×11’ oil painting in Rome depicts the moment when Jesus Christ inspires Matthew to follow him and become an apostle. In the painting, it’s not clear which one is St. Matthew. Is it the young man hunched over the coins? What about the main pointing at himself to ask “me?” Art historians have often said Caravaggio left it open ended for the viewer to interpret that the calling can be for anyone.

I use this piece of art not as religious evangelism but perhaps career evangelism. This painting often reminds me of how people get called into management, and how ambiguous it can be where great future managers come from. Perhaps it’s the 10x engineer who points at himself and clearly assumes it’s him. But what if it’s the average senior designer who has a great emotional intelligence (EQ), organized, and really cares about people?

Since it’s what I have the most experience and observation in, the purview I’m going to share is primarily design management, though I believe this applies to many other functions and disciplines as well.

The candid truth is that there are a lot of managers in positions who shouldn’t be. It’s not to point fingers as they come in many forms and they come in many forms. Perhaps it is someone at an early startup and fell into management as the company grew. Some pursue management positions for personal gains and have more perceived influence. As we ponder who would make good managers, we also must ensure that people who have a desire to thrive as individual contributors and leaders have incentives to do so.

The system often incentivizes people to go into management for the wrong reasons. There’s often a pay bump in becoming a manager. I believe that’s the wrong incentive, but that’s a different blog post.

At Webflow, we have individual contributor (IC) designer tracks that have parity with manager tracks, both in pay and influence. Leadership is a trait both managers and individual contributors have. If we’re going to fix the management pipeline, then we need to ensure individual contributors have clear and equal tracks. Buffer has a great article about their individual contributor career track.

“There is no success without a successor.” — Peter Drucker

The core problem I view is that there is a substantial gap in the management pipeline for new managers. As experienced managers and leaders in the industry retire (and they will at some point) there needs to be a clear investment for new managers to take the mantle.

A lot of managers transition into lateral positions at different companies. Roughly put, the same people are getting the management jobs, and not all of them are good managers. At this state, these managers will continue to fail up if there isn’t any dilution of the talent pool.

While this is happening, some of the best potential managers may be neglected from pursuing management, both by external forces and perhaps themselves. The biggest problem I see is the lack of encouragement from others for them to pursue management. In a land of bad-to-middling managers, sometimes people who would be great managers don’t see themselves in management positions because the people they do have as models aren’t who they want to be.

The industry needs good managers, which is not necessarily managers who have been doing it for a long time. The management pipeline needs to be refreshed from time-to-time with new people to take on the responsibility.

Hiring is important to get right at a company. Make the right move and you might find the person who is going to shift your team and elevate them. Make the wrong hire and it can be costly and dire. The impact is felt even higher for management and leadership roles. It’s no surprise then that companies are seeking methods to de-risk the hire.

I’ve often heard in many conversations with people considering management state that they want to pursue it to mentor and have more influence. It’s understandable how people might feel this way, however, it’s not good motivation to enter management. When you are in a higher leadership position, your role is more motivation and coaching than influence.

I firmly believe that some of the best new managers are currently individual contributors who have not considered management or shied away from it.

If you would have asked me a decade ago about people managers, I would have laughed. Never would I have imagined taking on a role as an introvert where the majority of the responsibility is dealing with people. My motivation then was to strive to be the best individual designer.

Though this clearly varies based on company and industry, I’ll try to boil it down to the essentials based on experiences I’ve had and observed. At the core, a good manager is someone where their highest impact is focused on developing people, processes, and systems that provide farther value than what they can achieve as an individual. Your focus transitions from heads down to heads up.

Clearly individual contributors also care about other people, however, the success of others is one of the core performance indicators in management. If you find joy working with people to enable them to be better at their job, management is a great place to do that.

The turning point for me was when I realized that focusing on spending time with other designers to help them get better brought me so much more joy than heads down time to explore a new project or prototyping tool, which I was very much in love with. Seeing where people started and witness their development became what I cared most about.

You care about people but your mission is that of the team. The team is your metaphorical product and you’re responsible to strategize, unblock, and scale. Empathy and advocacy for your people is the natural start of being a manager. However, to be a strong manager, you will have to thoughtfully balance the needs between every human and the team.

As a manager, you are now a builder and maintainer of people and systems. The responsibility of a manager is not to be good at everything, but to ensure the team is effective at everything.

The greatest system design challenge in the history of humanity is getting people to work together effectively.

If I’ve peaked your interest, here are some things to think about to prepare for the calling. The trick is to distribute your impact and influence as you’re a high performer to transition into a higher scale role. There is no shortcut to management. Be sure you’re a consistent and high performer at an IC level. The trick is to convey that your time can be maximized as a force multiplier.

Remember, if you don’t like management, you can always go back to being an IC in your career. There is nothing wrong with that. There are different layers of management, and you don’t have to keep climbing the ladder. Find the purview that gives you the most joy. If you enjoy first-line management, you don’t have to climb all the way up to executive. They have different roles and responsibilities.

Even if you have never thought about it, I encourage you to dip your toe and get some taste of management. You may find it be the calling you never expected.

It’s often said “the best ability is availability.” In order for people to champion your management track, you must make it known to people you’re considering it. This sounds obvious, but crucial. If you never speak up, people might assume you prefer to be an IC. Here are some ways to dip your toe into management.

The hardest gap to fill is to show people you would make a good manager when your resume has only been as an individual contributor. Identify a gap and volunteer to take it on with an action plan. An example of a process project could be a proposal to improve a design review process during critique or drafting a standard operating procedure for the team (SOP). As you take on process and team tasks capture impact metrics on the return on the time invested in you working on such things.

Note that I didn’t say mentor. If you don’t have any, mentor ones externally. There is no shortage of new designers looking for a great mentor and sponsor.

If you want to get a taste of management, then you have to do it consistently and be involved. Mentorship is great, but it’s a different type of focus. To get a taste of day-to-day management, coach someone more junior for them to take action, follow up and keep track of progress.

If you don’t have junior people on your team or company, work with people externally. I assure you people will be thrilled for the time you offer up.

It’s not too soon to start thinking about a management track in your career. However, give yourself time for the opportunities to form for you. Your career is a marathon, not a sprint. Start prepping for the opportunity and it’s not too soon to commence.

What does your heart and intuition tell you? If you sense a signal, dip your toe into management. Reach out to leaders to get their advice. If you’re interested in talking about it I’m happy to discuss personally or connect you with an advocate.

Remember, you don’t have to make a decision right away, though I encourage you to start exploring those capabilities. Accrue evidence as you begin the management dialog.

Take a moment and ask yourself, “What if the future cohort of great managers and leaders includes me?”

Special thanks to Julia Ferraioli for editing.

If you ever want to discuss management, shoot me an email and I’d be happy to discuss with you or connect you with another experienced manager.

A great excerpt from the book “Designing for Emerging Technologies” and the need for designers to tinker and learn.

Designers will need to understand the implications of science and technology for people. To do this effectively, we must be able to immerse ourselves in new technical domains and learn them quickly. Just as our understanding of and empathy for people allows us to successfully design with a user’s viewpoint in mind, understanding our materials, whether they be pixels or proteins, sensors or servos, enables us to bring a design into the world. To achieve this, designers need to be early adopters of technology, learning constantly. —Designing for Emerging Technologies